By Chris Maclay. This also heavily references Li Jin’s Unbundling Work from Employment article, which is worth a read in itself.

Apologies for the clickbait title. I don’t want to create fear when everyone is already losing it about a slowing economy, a heating planet, and a shrinking of chapatis. I also hate myself for pushing a false understanding that jobtech is just about ‘jobmatching’ (more on what jobtech is here and here). But it is an interesting question to ask, and one that needs consideration in the context of a slowing global economy.

It also needs consideration in the context of labour market trends across Africa. TL;DR; there simply aren’t enough jobs. The IMF reports that an average of 9 million jobs in Africa have been added to the economy each year since 2000, significantly short of the 20+ million people who will be hitting working age each year over the next two decades. As Louise Fox and team at the Brookings Institution explain, “Africa’s ‘youth employment crisis’ is actually a ‘missing jobs crisis’.”

From a start-up perspective, you might call this a case of a frustratingly small TAM (total addressable market). And a TAM that could get smaller as the continent teeters on the edge of a potential global recession. So what do jobtech platforms look like in the context of no jobs?

The truth is, that most jobtech platforms were seldom about formal sector ‘jobs’ in the first place. In Africa, they have tended to work most effectively in markets that have historically been termed as ‘informal’. Even in more established markets, jobtech platforms have played a critical role in helping people navigate the ‘unbundling of work from employment’ as Li Jin calls it, in her excellent blog of the same name.

Western labour markets have started looking a lot more like African labour markets over the last decade. Jobs are not ‘jobs’. Work is not ‘employment’. Rather, people are increasingly managing a portfolio of work, tying together different income streams into a mixed livelihood. Historically in Africa, this might have included day labour and farm work. Today, that could include some sales on an e-commerce marketplace, or a few days (or hours) of work on a gig or freelancing platform.

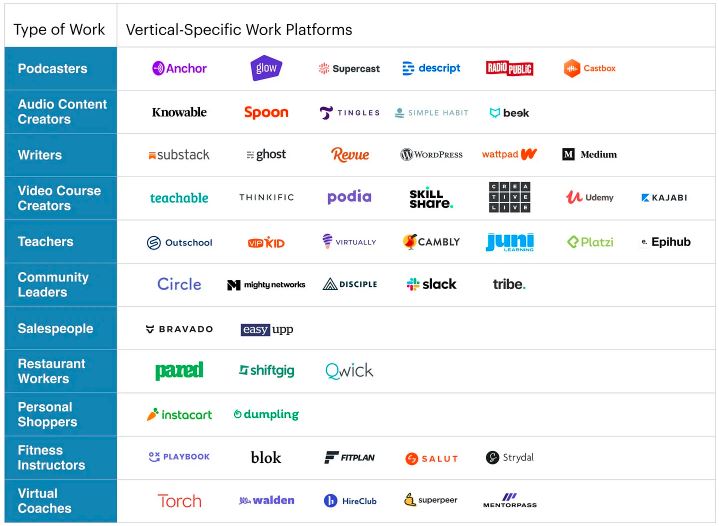

Jin emphasizes how the internet has turbocharged this unbundled employment, enabling people to move from employment into entrepreneurship which, she says, satisfies people’s ‘innate human desire’ for more freedom, fulfillment and career control. Ignoring the accuracy or not of the above statement (Jin has clearly drunk the full pitcher of gig economy Kool-Aid), Jin goes to thoughtfully characterize such unbundled work platforms under two categories – ‘horizontal’ (sector-agnostic) and ‘vertical-specific’ (designed for specific industries). She gets particularly excited about the latter of these, as they “can actually expand the market of workers who can participate in a certain industry by honing in on and removing the obstacles for prospective workers.”

Having worked in the youth employment space for much of my career, I remember when microfranchising was seen as the silver bullet for youth employment. For those of you not familiar with what ‘microfranchising’ looks like, but are familiar with Nairobi, this is the answer:

Source: Nyongesa Sande

The silver bullet logic was that these business-in-a-box models reduced many of the likely reasons for business failure among young and low-skilled individuals, giving them access to a trusted brand, standard products, pricing, supply chain and more. This also reminds me of my time at Lynk, the Kenyan gigmatching platform, where we found ourselves building layer upon layer of operational process (standard tools, materials, service delivery process, pricing) and explained that what we were doing was providing the ‘entrepreneurship infrastructure’ for blue collar workers to thrive.

This language of infrastructure seems to be all the more relevant to the emerging themes around jobtech and the unbundling of work from employment. Li goes on to talk about the other (US-based) platforms that excite her. Dumpling provides all the infrastructure (website, client-facing app, financing, coaching) for people to set-up their own on-demand grocery delivery businesses. CALA provides the infrastructure (e-commerce interface, supply chain, financing) for designers to launch their own apparel lines. Wonderschool provides the infrastructure (customer-facing websites, curriculum planning tools, marketing, financing, and backend administration tools) for at-home daycare providers. There’s more:

Source: Li Jin

I’d suggest that this is probably what jobtech thrives at when there are no jobs, or a lack of ‘jobs’. A top-down platform is unlikely to solve a shortage of jobs in an economic downturn, but a platform that provides entrepreneurs with the tools and infrastructure that they need to navigate the uncertain terrain of an economic downturn could be. Jin explained that many of these platforms emerged in the US during COVID, when over half of the US population found themselves jobless.

As a side tangent, this is not to say that jobtech platforms cannot be employment creating themselves. Jin emphasized how vertical-specific platforms are particularly good at creating new markets of consumption. At Lynk, we used to guess that half of our jobs replaced a service that would have been done anyway (although we gladly said that it was more professional and better-paid), but half were genuine job creation, as they moved customer non-consumption into consumption. It could be so stressful to get a table made from a local carpenter, that people would buy a Chinese import. Or it would be so difficult to get a plumber to fix the leak under the sink that it was left to keep leaking.

‘I’ll do it tomorrow’

At Lynk though, we never really set-up our platform as an infrastructure play though. Rather, we became more of an aggregator that provided the necessary infrastructure to enable quality commoditized service delivery, than a true platform for service providers to manage their businesses. Jin seeks to emphasize the difference in her article, and points out that vertical-specific platforms look a lot like SaaS. There are definitely questions about whether real SaaS-type models are feasible right now for many microenterprise verticals in Africa, where microentrepreneurs are more informal and less tech-savvy, and platforms often need to deal with so many operational hurdles to deliver with quality (more here). But likely, they just need more heavy adaptation for the context, in the way that Wasoko / Marketforce / TradeDepot etc etc have done for FMCG supply chain. Sayo Folawiyo, CEO of South African home services marketplace, Kandua, says that this is exactly what they’re working towards – ‘HustleOS’, as he calls it. It also says that this really is the only route to scaled jobtech in Africa: “You are either a vertical or infrastructure. The middle is no man’s land.”

Christopher Maclay is the global Director of Youth Employment at Mercy Corps. He was previously COO at Lynk.

0 Comments