by Garvit Goswami & Nick Markham

TL;DR: We planned a niche experiment, but uncovered a large (but hidden!) ecosystem. 350+ startups applied, covering migration corridors from Africa to the Gulf, Europe, and further afield.

In late 2024, at the Jobtech Alliance, we started exploring labour mobility as a sector. We wrote about why we need to look beyond Africa in terms of job creation. We then dug deeper with our investment support for two labour mobility platforms: AEDILO and Velocity.

The role of the private sector in enabling quality migration is poorly understood. We knew there was much more to learn. From a distance, it is hard to see the difference between the social entrepreneurs building safe and dignified migration paths, and the numerous agencies moving people at the lowest cost, often setting migrants up for precarious work and/or burdened with debt before they’ve even started.

That’s what led us to launch our Cross-Border Jobs Startup Competition. It was our way of saying, “If you are building real infrastructure for physical mobility, show us what it looks like.” Our goal was simple: to stop talking about labour mobility in the abstract and listen to the people actually moving African workers across borders.

We expected a hundred applications at most, with maybe ten that would really teach us something. Instead, more than 350 poured in; we were delighted to have been wrong in our expectations. The volume alone told us something important: this is no longer a niche corner of jobtech. There is a real ecosystem forming around labour mobility for Africans, but not one that many people have been able to see it clearly…until now!

In this blog, we share what we learned from running the competition, naming our three winners and detailing what made them stand out.

Why labour mobility

Every year, 10-12 million young people enter the labour market in sub-Saharan Africa, but the continent creates only about 3 million formal jobs annually. So domestic demand for labour is deeply, structurally constrained. And with sub-Saharan Africa set to remain the world’s youngest region for the foreseeable future (with median age of 30 until 2100), domestic markets may simply not expand fast enough to absorb this incoming workforce.

We have the literal opposite picture in Europe and the Gulf. Ageing population with worker shortages in most sectors, from nursing to logistics, to construction. A rapidly shrinking working population in the US, China, Japan, South Korea and all of Europe, estimated to contract by 340 million workers by 2050. Hundreds of thousands of unfilled roles in Germany alone, projected to rise to 5 million by 2030. Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states are taking in 19+ million expatriate workers, including in hospitality, delivery, security, and care work, among others.

African talent is young and ready for this rising global demand, but the pipes that connect the two are fragmented, risky, and underinvested in. Most workers have to self-finance every step of the journey, often through expensive informal loans that result in significant drop-offs long before deployment. But when labour migration works, the impact can be extraordinary. A worker can increase their income 4 to 10-fold in a single move, while their remittances ripple through families and communities.

We are certainly not labour mobility evangelists. We are very aware of the risks. Exploitative brokers. Opaque fees. The “worker pays” norm in corridors even when the law says the opposite. The risk of health worker shortages in African countries that already have fragile healthcare systems.

So we went into this competition with an open mind. We know labour mobility presents an enormous opportunity if done well, but it depends entirely on how responsibly the pathways are built. Our question was not “Is labour mobility good or bad?” but “Who is building credible, fair, and corridor-specific solutions, and what can we learn from them?”.

We knew we could not do this alone. Labour mobility looks very different depending on where you sit, so we pulled in partners who see the parts we do not:

- Labour Mobility Partnerships (LaMP) brings deep corridor and sector expertise and a real, macro-based understanding of how mobility systems succeed or fail.

- The Challenge Fund for Youth Employment (CFYE) sees the youth employment landscape from a funding and policy angle.

- The International Organization for Migration (IOM) brings decades of migration experience and the reality check that only a field organisation can offer.

- Tech Safari helped us reach operators we might never encounter through our usual networks.

What 350+ applications showed us

As we filtered out all the applications, they stopped being a pile of decks and started to look like an X-ray of the sector.

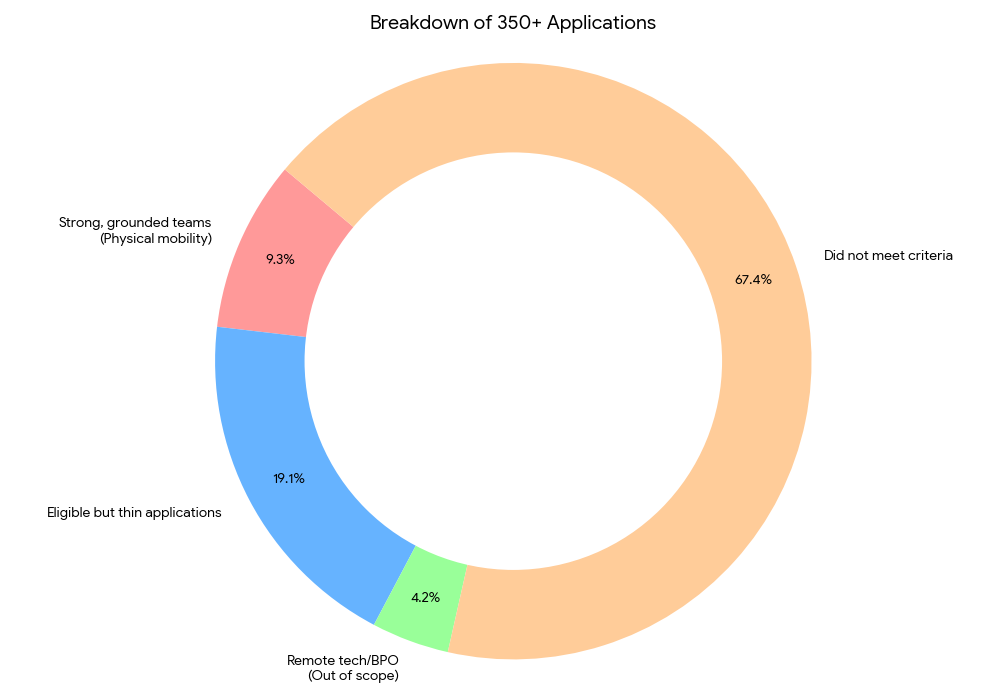

We identified three broad groups of applicants:

- A surprisingly large number (~33) of strong, grounded teams working on physical labour mobility across specific corridors and labour segments. These were the ones who live in visa processes and embassy queues, contract negotiations and sourcing workers. These founders were solving the messy part of labour mobility.

- Eligible but thin applications (~68) that had the right vocabulary and a polished presentation, but had very little real experience on the ground. We could almost see our own language from previous blogs reappearing in some of these applications.

- Remote tech talent, BPO, and global freelancing platforms (~15) that were not touching on physical mobility at all. Some of these were excellent startups in their own right, and very relevant to our wider digital work focus, but they were not in the scope of this competition.

A total of 240 applicants did not meet the criteria for shortlisting, as they were not migration-related at all.

What we learned about corridors, models and the biggest challenges

Reading applications back to back, the corridor logic became very hard to ignore. We always knew that on paper, corridors matter. But seeing this logic play out repeatedly, and with such specificity, across hundreds of teams, provided us a new level of clarity. It showed us how each corridor creates its own incentives, risks, business models, and worker realities. And more often than not, the strongest applications were the ones that deeply understood those corridor-specific dynamics and tailored their solutions accordingly. Each corridor presented a different opportunity and came with its own stack of problems:

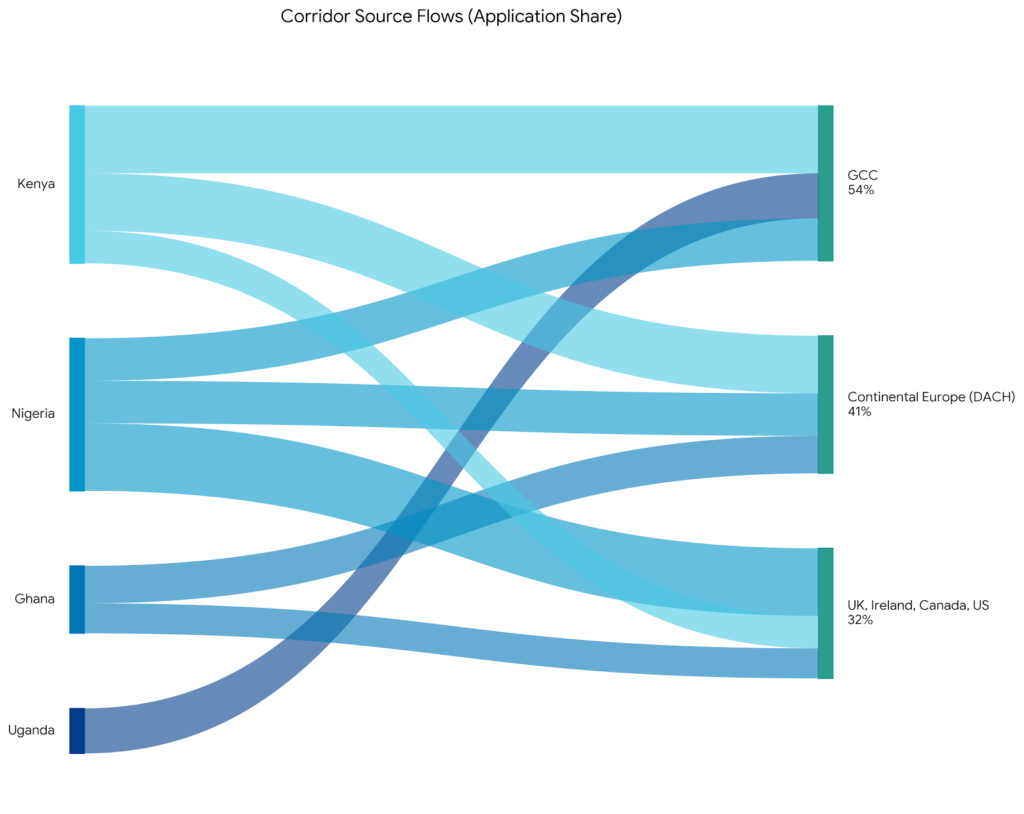

- Continental Europe, particularly the Germany, Austria, and Switzerland (DACH) corridor was the most common one (41% of applications). Within this corridor, nursing was the dominant labour segment. These platforms live and breathe licensing rules, language exams, and slow but highly regulated processes. Their businesses have to become training and compliance machines. They describe workers spending months in language classes and the painful drop-offs before reaching B2 level. These platforms have a two-fold focus: training (language, skills verification); and placements and demand.

Kenya was the top source country (56.1% of all applications targeting this corridor), followed closely by Nigeria (41.5%) and Ghana (36.6%).

- The GCC corridor (54% of applications) told a different story, as it is oriented primarily towards fast deployment. Whether it was Kenya to the UAE or Uganda to Qatar, blue-collar workers made up the bulk of the movement. It is also the corridor seen as the most risky, given exploitation issues and well-documented vulnerabilities. Everything in this space revolved around worker safety, employer behaviour, contract transparency, and how quickly people could actually be deployed.

These teams are not running matching platforms and not aiming to just solve for information asymmetry; they are operational machines sitting in the middle of the process handling contracts, paperwork, onboarding, welfare checks, and everything else that tends to go wrong in fast-moving deployment models.

The platforms operating along this corridor primarily sourced from East Africa, with Kenya being the top market (50.0%), followed by Uganda (33.3%) and Nigeria (31.5%). While the applications demonstrated pathways from all major African hubs, East Africa was the leading origin for the high-volume labour demand of the GCC.

- The UK, Ireland, Canada, and US corridor (32% of applications) has models mostly built around skilling, exam preparation, and study-to-work routes. While the rules governing this corridor are clearer, the process is still unduly long, expensive, and demanding for workers.

This corridor is overwhelmingly sourcing talent from West Africa, with Nigeria mentioned by an exceptional 84.4% of applications, making it the single most important source for the high-skilled digital and professional services talent required along this corridor. Kenya (40.6%) and Ghana (37.5%) were the other top source countries.

Diagram: % of applications for the leading corridors, including their main source countries.

Intra-African labour mobility was mentioned by 41% of all applicants. This included the Nigeria-to-Egypt care sector. However, we did not see any platforms that had actually facilitated intra-African movement of people across borders. The nascent stage of this corridor might very well be dwarfed by the promise of the above.

We did not receive any applications targeting Francophone countries (e.g., France as target, Cameroon as source). This likely reflects the limited visibility of our outreach in these markets, language constraints, or the smaller size of the jobtech ecosystem focusing on Francophone regions.

Across all the corridors, the same challenges kept showing up. Workers struggle to cover early costs, agencies still run critical processes on spreadsheets and messaging apps, and almost nobody has built proper support for workers during the first, most turbulent few months after arrival. Safeguarding was talked about often but rarely embedded in solutions. This serves as a reminder that while the sector has energy, the underlying infrastructure is still pretty nascent.

How Luka, Propela Health and WorkAbroad rose to the top

So, what made the winners stand out? They were building directly within the most acute pressure points and addressing the biggest structural gaps.

Luka tackles the pre-departure financing bottleneck, focused initially on the East Africa to GCC corridor. Not abstractly, but in a way that matches how workers actually plan, save, and repay. Its focus is on the workers who are in highest demand globally, but have the lowest access to fair financial products. The competition made it clear that without reliable, ethical finance at this stage, a huge amount of potential migration dies before it even starts. Luka is one of the few platforms that can unlock this crucial stage without pushing people into debt traps.

Propela Health gave us a very clear, end-to-end view of what a safer healthcare mobility pathway can look like when designed with workers (e.g., nurses), not just employers, in mind. It has made a deliberate choice to focus on English-speaking markets (South Africa for supply, the UK and Ireland for demand) first, to avoid the often challenging German language requirements. That one decision dramatically reduces drop-off and sunk costs for workers, while still connecting into real global demand.

WorkAbroad took a very different path, focusing on the existing agencies and employers in Europe who desperately need better systems, not more candidates. Most labour mobility failures are not caused by a lack of (qualified) workers. They happen because the process of moving a worker across borders is incredibly paperwork-heavy. Every placement requires dozens of documents, government forms, verification steps, and back-and-forth between employers, agencies, training providers and regulators. Most of this is still handled manually through email and spreadsheets. One mistake or missing document can stall the entire process for months. These delays cost employers money and push workers into drop-off or irregular routes. That is why we see documentation and compliance as the silent killers of mobility pathways. Without a solid B2B infrastructure layer that automates and tracks these steps, even the best worker-facing platforms eventually hit bottlenecks they cannot control. This is exactly what WorkAbroad is solving for.

How this all connects back to our wider labour mobility work

The competition was the first step in a longer journey for us. It gave us a clearer view of where the real friction sits in cross-border work, and it will feed directly into our upcoming sector scan on jobtech and labour mobility. That work will bring together insights from research, partners like LaMP, CFYE and IOM, and the platforms we already support, along with what we have learned from this new wave of founders.

The goal is not to scale migration for its own sake; it is to strengthen the systems, partners and models that can make mobility safer, clearer and fairer in practice. In the months ahead, we will work closely with Luka, Propela Health and WorkAbroad as they refine their models. We will also bring a wider group of operators and partners into the same room in a small, practical gathering early next year. The competition showed how many teams are trying to solve similar problems in isolation, and how much can be gained from sharing corridor insights, mistakes and infrastructure.

We have no interest in promoting labour mobility blindly. We care because millions of young Africans are entering labour markets that cannot absorb them, while global demand continues to rise. If Africa is going to play a meaningful role in the future global labour market, the routes people travel need to be far easier and safer than they are today. This competition helped us see the picture more clearly. The work now is to help shape what comes next.

0 Comments