Author: Chris Maclay

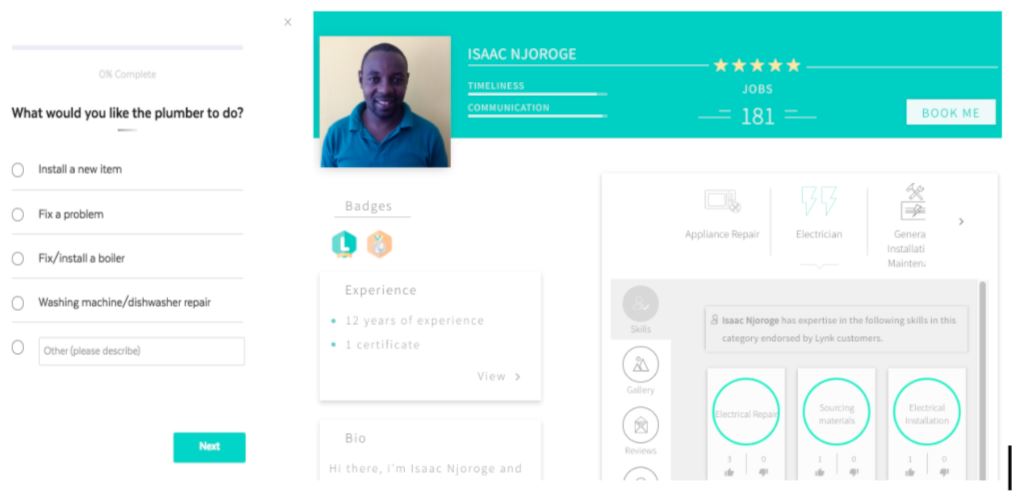

Lynk is a service marketplace based in Kenya, providing services to households and businesses in dozens of categories from furniture, to beauty and installation, repair and maintenance. Lynk was founded in 2015 by Adam Grunewald and Johannes Degn.

Lynk pivoted operational models multiple times as it sought a model to effectively deliver a services marketplace at scale in Nairobi. In this Lessons Learned (The Hard Way) edition, you’ll learn about Lynk’s experiences:

- Deciding on a lead gen vs full service model

- Deciding on an auction marketplace vs a standardized model

- Operational challenges and possible solutions for service marketplaces in Africa

Lynk v0: the experiments

The biggest question for Lynk to answer in its early months was whether the marketplace would be ‘lead gen’ (where the platform’s role is just up to the point of connecting a service buyer to a service provider – like the yellow pages) or ‘full service’ (where the platform is responsible for the entire service delivery – like Uber). While Lynk initially modelled itself as a ‘LinkedIn for the LinkedOut’, overcoming the lack of transparency in the sector by enhancing the visibility of vetted professionals, it quickly learned that information asymmetry itself was not the biggest problem – too many jobs still went wrong for well-recommended or vetted individuals, and customers were not willing to pay for the services of vetting and enhanced convenience alone. So, unlike Thumbtack in the US – which reached unicorn status on the back of a lead gen model – Lynk decided that a full service model better satisfied customer demand in a Kenyan context.

Lynk v1: the open quoting model

Lynk settled on its first operating model, which replicated the first iterations of most global services marketplaces such as Thumbtack and Taskrabbit in the US and UrbanClap in India: a customer makes a request. Based on some form of algorithm, the request is shared with the most suitable vetted professionals (or ‘Pros’), who are then invited to quote for the job. The customer receives the quotes, who can view the profiles of the bidding Pros, and select who to work with. The service is delivered offline, and payments are made through the platform after the service is completed. Simple.

Not so simple. The open quoting model faced a number of challenges, which were each manageable at a small scale, but became harder to manage as the service scaled:

- Quote process delivers a slow customer experience: when a customer makes a request, it means they want to book a service at that moment. Pros would be slow to quote because (i) they were busy on jobs (ii) some were unfamiliar with such an up-front quoting system (iii) particularly if they had previously been unsuccessful with quotes, they were likely to deprioritise quoting in their busy days. While Lynk promised quotes within 24 hours, this was operationally difficult to maintain with open quoting. Regardless, for certain services (such as beauty services), customers wanted to book immediately rather than going through the delayed quoting process.

- Lack of price transparency and consistency: The lack of up front pricing meant that Lynk (and its Pros) wasted time quoting for customers who were merely window shopping, or who would request quotes for things which were way out of their price range because they did not know how much certain services actually cost. Variable pricing also did not work well for repeat or business customers – ‘if I paid 22 shillings per square meter for painting last time, why am I now paying 24 shillings?’

- Inaccuracy of quotes: Maintaining appropriate and fair prices was a consistent challenge for Lynk. In some cases, this was due to inaccuracy or incompleteness of customer requests – a Pro would turn up at a site, and the customer would expect more than had been quoted for. In other cases – particularly after quoting for jobs requiring a site visit – it was due to Pros over-quoting once they saw (for example) that the client lived in a big house.

- Too many variables: Customers would request for a huge variety of services, often for hugely niche skill sets that didn’t exist in the market, or for things that were completely impossible to deliver. Pros would often accept jobs, knowing or not that they lacked the specific skills, in the hope that they could do the work or subcontract out the part that they could not do. Though Lynk would vet for both technical and soft skills, they could not vet for each and every activity that could be performed. This model risked setting up Pros and the jobs to fail.

- Cold start problem for Pros: The model of demonstrating ratings and previous reviews worked. Remarkably well. Too well. Customers would generally pick the Pro with the highest number of jobs completed and/or ratings, particularly over new Pros with zero ratings. This made it hard for new Pros to get their first jobs, and sometimes meant that new Pros quickly churned after quoting (and failing) for their first few jobs.

Lynk v2: the standardized service model

After working through a wealth of fixes to respond to the above – from endlessly reviewing the questions included in request flows for customers, to manually checking all requests and quotes for suitability, to creating a pool of customers benefiting from discounts to test out new Pros. None of those fixes created the drastic increase in quality and operational scalability that Lynk desired. The greatest shift came through a process which many other service marketplaces including Taskrabbit and UrbanClap embarked on: standardization. This involved the following:

- Limiting options: Customers could only pick from a strict set of predetermined services or SKUs. Anything beyond those services was unavailable. Rather than being assigned to a ‘category’, Pros were now assigned to individual products or SKUs which they were able to deliver upon.

- Setting prices: Pricing was upfront for ‘simple services’ (like cleaning or beauty), or based on a predetermined time-based calculation for more complex services (like electricians), based on fair market rates.

- Standard delivery process: To ensure that Lynk services were delivered with a consistent customer experience, Lynk standardized its services into a core step-by-step service model, from the greeting when a Pro arrived at the house, to the method of clean-up at completion.

- Standard dress and tools: To enable a standardised service, Pros were provided with the outfits, personal protective equipment, tools and equipment needed for the services they were assigned to. These were subsidized by Lynk, and Pros paid off their percentage through work completed on the platform.

- Standard materials: Lynk developed partnerships with reputable suppliers, to ensure that Pros on Lynk jobs always used the highest quality materials.

- Improved marketing and customer filtering: The model meant that Lynk could sell a fixed price service so there was better customer clarity and filtering at the top of the funnel. Customers could now browse available services, ensuring a greater alignment of expectations, and stimulating demand.

- Enhanced customer experience: Standardisation reduced wasted time for Pros and Lynk providing quotes, and enabled customers to get a Pro at their house within two hours of ordering. Additionally, standardization provided a more consistent customer experience (and more attuned to customer desires, as the service model had been designed based on extensive customer research), and customer satisfaction drastically increased.

- Operational simplicity and automation: Customers were now buying a service rather than submitting a request, enabling pre-pay. Then, rather than picking from a choice of Pros, the Lynk system was simply able to fully automate Pro assignment, offering jobs to Pros based on its algorithm with a simple Yes/No SMS response. This additionally overcame the cold start problem, as new Pros could easily be assigned jobs within hours of signing up. It turned out that customers didn’t need to choose a highly rated Pro as long as they knew that Lynk had vetted them and could guarantee the service. It also unlocked the ability for customers to develop trust in the brand as opposed to a specific Pro.

- Eased recruitment and Pro onboarding: Standardization made recruitment easier as Lynk needed to vet people for less things – Pros also didn’t need to be as good at things like quoting, and they were vetted and assigned to individual products or SKUs rather than whole ‘categories’ meaning that their experience needed to be less broad at the point of onboarding. They could then learn new products through Lynk’s Academy (more in a later episode) once on board.

Lynk v3 and ongoing evolutions

The standardization model drastically improved quality, customer satisfaction and operational scalability at Lynk. But it did not solve all problems, and naturally created new ones. These will not be explored in this brief (more in later episodes) but will be briefly summarised here:

- Some services are easier to standardize than others: While the model worked easily for services like beauty, and furniture items could be turned into purchasable SKUs, it was much harder to standardize for plumbing, electrical, or other services with a wealth of variability.

- Shifts in operational bandwidth: While many operational hurdles were overcome, new operational requirements around maintaining inventories and relationships with suppliers (in dozens of categories) arose.

- Transport: An ongoing challenge at Lynk was the cost and time of transport (which can represent a significant percentage of the cost of labour). Lynk had to maintain a balance of supply-and-demand of Pros across dozens of categories – enough demand to keep Pros interested and motivated, and enough supply to ensure that Pros were available. While Pros were spread across Nairobi to reduce transport, distance to customers (who often lived in very different geographies to the Pros) could be extensive, causing delays in Nairobi traffic or high transport costs.

- Customer variability: Despite optimizing for the best customer experience – from service process to premium suppliers – customers for home services (particularly B2C customers where service delivery happened in someone’s home) had hugely variable desires. Whereas the variability for desire of taxi services was relatively low (Uber, UberX, UberXL), variability for home services was huge. Some customers wanted a cheap fix rather than a comprehensive fix with quality materials. Some demanded a nail varnish brand that wasn’t available. Despite clear messaging on what was available, customers in intimate services demonstrated consistent variability.

- Continued Pro unreliability: An ongoing frustration at Lynk was that, the same Pro who had reliably completed 500 jobs with a five star rating, would ‘go mteja’ (disappear and be uncontactable) on the 501st. Although Lynk’s operational processes had drastically increased compliance, deep-seated issues of unreliability in many of Lynk’s trades were never fully overcome.

- High costs of Pro vetting and training: The above required huge efforts to recruit, vet, and train Pros. Partnerships with vocational training partners never took off, and Lynk had to establish a Lynk Academy for recruiting, vetting and training Pros.

- Customer social prejudices: Customers, often from significantly higher social classes than the Pros, would often unfairly mistrust tradespeople, assuming that they were cheating them or delivering low quality work, because of previous bad experience or communication challenges.

Do you want to know more? Check out the video below from Adam’s Jobtech Alliance webinar in early 2022, or contact Adam Grunewald, Lynk CEO, [email protected]

The author was COO of Lynk from mid-2017 to early-2020.

0 Comments