Authors: Timothy Asiimwe & Chris Maclay

Ecosystem infrastructure? Ecosystem stack?

While getting feedback on the Jobtech Alliance strategy, we spoke with many fascinating and impressive ecosystem builders. Karan Chopra, founder of Opportunity @ Work (a social enterprise which aims to ‘re-wire the U.S. labor market’) and Advisor at Google’s moonshot X department, explained that one of the things we should consider is what the technological infrastructure might be, which catalyses more successful and impactful jobtech on the continent?

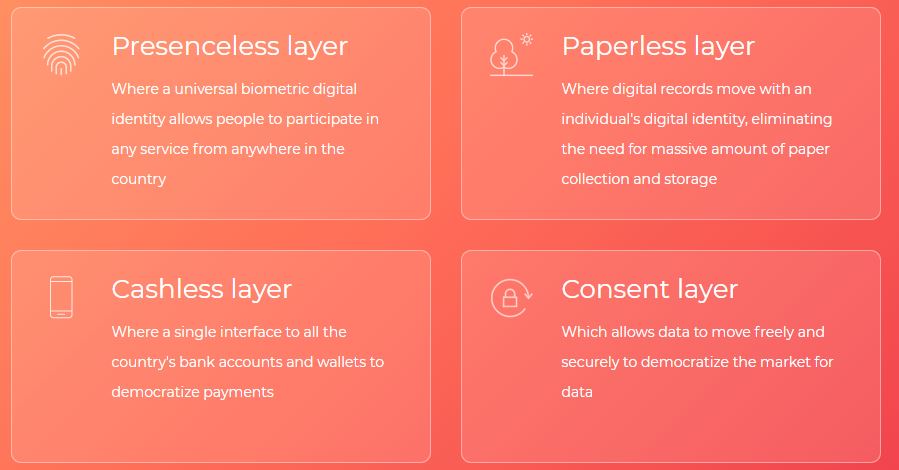

More recently, we were listening to The Flip podcast, where host Justin Norman talked about IndiaStack – the infrastructure (much like Chopra asked) which the Indian government built to catalyse the development of financial products and enhance financial inclusion. IndiaStack defines itself as “a set of APIs that allows governments, businesses, startups and developers to utilise an unique digital Infrastructure to solve India’s hard problems towards presence-less, paperless, and cashless service delivery.” If has four components:

In the podcast, Norman asks what the Africa Stack might look like to catalyse the growth of fintech and enhance financial inclusion on the continent. Moving back to Chopra’s question to us, we realise that the question we as a community need to answer is: what does the Jobtech Stack look like?

Is the jobtech stack really feasible?

What could a jobtech stack realistically achieve? With the right infrastructure, a stack of digital assets built for the jobtech sctor could feasibly help make jobtech solutions:

- more viable and scalable by reducing operational and financial costs/barriers to entry

- more inclusive by reducing barriers to access

- more impactful by enhancing services, giving jobseekers more control and use of their data, reducing costs and more

- probably more things we haven’t thought about

Efforts have been made in adjacent sectors and internationally to work on comparable ‘stacks’ (just to be clear, the term doesn’t have any more than metaphorical relevance to Sayo Folawiyo’s recent Jobtech Alliance blog post about taking a ‘full stack approach to jobtech’). One of the best examples of the attempt to build a foundational stack which enhances inclusivity of an emerging sector comes from the financial inclusion space, where Google, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, Coil, Modusbox and others, collaborated to build Mojaloop, and open-source platform which seeks to enhanced interoperability in payments systems to enable digital financial services for all.

Similarly, Farmstack is an attempt to provide open-source software for trusted data exchange in the Agriculture space.

In the jobtech world, there are a number of global examples of attempts to build individual pieces of the jobtech stack. In Sweden, the Ministry of Labour has a department called JobTech Development which provides APIs, datasets, standards and open source code for jobtech solution builders. They have also been exploring the possibility of building a Digital Backpack which enables gig workers to port their professional identity between different platforms. Similarly, a pilot with six platforms in the Netherlands (through GigCV) aims to provide an open standard for platform workers to download and transfer their reputation data between platforms. Also connected, efforts are being made by the International Council on Badges and Credentials to create standards in credentials for workforce development which could be used by jobtech platforms.

While many of the examples above were built by governments, non-profits, or as open-source projects, jobtech stack solutions could feasibly come in a range of different forms:

- Standards for use by different actors

- Open-source projects offering tools or APIs for others to use

- Commercial endeavours which offer APIs or composable solutions

- Probably more things we haven’t thought about

While these are all interesting examples of global solutions, what might the full jobtech stack look like in Africa? What might be the different pieces of foundational infrastructure that could catalyse more viable, scalable, inclusive, and impactful jobtech solutions in Africa?

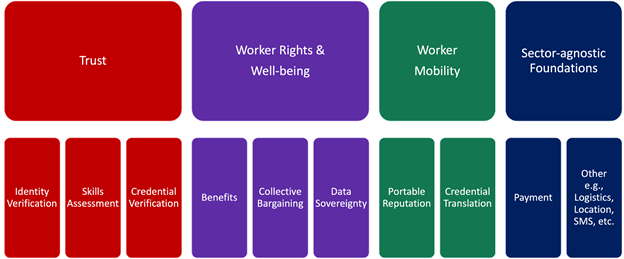

Our understanding of the jobtech stack

In order to understand what capabilities needed to be included in the jobtech stack, we utilised Clayton Christensen’s Jobs to done framework. After identifying the jobs-to-be-done and matching them with the required technical capabilities, what emerged is the diagram shown below.

Our current thinking is that the Jobtech Stack can be broadly classified into four layers: 1) Trust, 2) Worker rights and well-being and 3) Worker Mobility, and 4) Sector-agnostic foundations.

Sector-agnostic Foundations

We bring this up first to get it out of the way… it’s important to recognise that much of the ‘stack’ that jobtech solutions lean on are, and will continue to be, sector-agnostic. From Google’s location-based API that enables a plumber on a matching app to find their next client, to the payments infrastructure that enables them to get paid, jobtech benefits from a much broader stack of digital assets. There are definitely ways to make that stack more suitable for jobtech (for example, Mercy Corps has piloted the establishment of crypto-based payment rails for microwork), but this stack definitely exists multi-sectorally.

Trust Layer

Trust is the glue that enables work intermediation platforms to function properly. Before letting drivers onto their platforms, ride-hailing apps such as Uber have to first verify their identities and driving certifications. Similarly, home services marketplaces such as SweepSouth in South Africa carry out vetting procedures and skills assessments before letting providers onto their platform. For gigs or jobs in skilled trades, potential employers or service buyers might want to vet academic qualifications, work experience, quality of work output, test soft skills, or assess any number of other things. Jobseekers or entrepreneurs also crave the opportunity to demonstrate their trustworthiness, which can be critical for getting new work, or additional services like loans.

Despite trust being the glue of many work intermediation platforms, building professional trust in Africa does not come easily. When academic qualifications are easy to fake or pay for, can employers trust scanned certificates? Which academic qualifications are actually good anyway? What about in sectors where skills are learned without academic qualification? Beyond education, how can I trust this person’s reliability/timekeeping/legality/etc? These tend to be some of the biggest costs for jobtech platforms in Africa, particularly in skilled sectors, and have become operational barriers that could not be overcome by many failed jobtech start-ups.

What services could become part of a trust layer? What services could create better proof of trust in individuals’ professional skills and experience, and in doing so, enhance workers’ ability to find work, and platforms’ ability to give those people work?

Some examples of APIs already exist, which have the potential to speed up or at least lower the costs of identity verification, skills assessment and credential verification. In Africa, Smile Identity and Kiva Protocol are examples of organizations building identity verification APIs that enable jobtech platforms to seamlessly verify the identities of their users. Similarly, SAQA VeriSearch enables employers in South Africa to easily verify the qualifications of prospective employees. The trust layer also includes skills assessment tools such as Knack, as well as cryptographically verifiable credential protocols and standards such as Blockcerts and W3C Verifiable Credentials (VCs).

Worker Rights and Well-being Layer

The rise of new modalities of work such as on-demand and temporary work, as well as the increasing permeation of technology into our ‘work lives’ is opening up new questions around worker rights. For instance, “Should workers have the right to ask a company to delete all the data they have on them?” or “Should gig workers have a right to sick days, retirement benefits and vacation?”. Are there elements of a jobtech stack which could make jobtech platforms hardwired to respect worker rights and promote worker well-being? Or at least make it easier to achieve greater worker-level impacts?

The answers to some of these questions can be complex, given huge regulatory variances across geographies and jurisdictions. Nevertheless, some inspirations exist from outside the continent, such as Symplifica, which provides tools to make it easier for employers in Colombia to formalize their labour relationships with domestic workers, guaranteeing fair working conditions, and mandatory benefits including paid vacations, maternity leave, pension, severance savings and health insurance. Similarly, Nippy seeks to provide a range of career advancement and benefits to gig workers in Latin America. Another example is Worker Info Exchange, which enables workers to make data portability requests and to aggregate their data with other workers in order to leverage it as a resource for collective bargaining.

Worker Mobility Layer

Worker mobility is a critical building block for any well-functioning and inclusive labor market. Particularly in Africa, where few gig workers have CVs, work completed on platforms offer one of the only opportunities for using work history to get more work (see Trust layer). Unfortunately, many digital work intermediation platforms make it virtually impossible for platform workers to carry their earned reputation with them across different platforms. For instance, if a SafeBoda rider with a 5-star rating signs up for another hailing app, he would need to rebuild his reputation from scratch.

What services could enable workers to freely explore new opportunities or find their next role? Are there solutions that could enable workers to carry their data and reputation with them from one platform to another?

Worker mobility goes hand in hand with trust. Any solutions that increase trust will almost inevitably result in greater mobility. The W3C VC standard, for instance, ensures the compatibility of credentials issued by different platforms. That said, we think that trust is necessary but not sufficient in order to ensure true mobility. Systems need to be able to ‘talk to each other’ in order to ease worker mobility. One way to go about this is by creating standards that ensure interoperability between systems. As previously mentioned, GigCV is attempting to do this in the Netherlands. My Digital Backpack from Sweden, on the other hand, is building a ‘wallet’ that enables workers to collect and transport their reputation data from one platform to another. In Africa, Yoma is seeking to provide a portable skill and identity wallet that can be used across platforms.

What’s next?

As the Jobtech Alliance, we hope to explore more into this topic over the coming months and years. The thoughts above are to stimulate ideas and conversation – help us to refine them with comments and feedback! Initially, we will just try to understand it, and will explore the individual stack components in greater detail in subsequent posts. But we will also try to identify how to stimulate individual elements of the stack to get built – while we don’t expect to have the resources, capacities, or mandate to build a full stack like IndiaStack for jobtech across a whole continent, we hope to work with different actors to see how to encourage elements of this stack to be built. Stay tuned!

Timothy Asiimwe author is the co-founder and CTO of Ugandan jobtech start-up Sellio.

Christopher Maclay is Director of Youth Employment at Mercy Corps.

Chris and Tim, this is great! I would flip the model, where the foundational layer carries all the others with trust being a cross-cutting layer. In Africa, Trust as part of our cultural fabric is still the one determinant of a platform’s success, that is why WhatsApp is a greater gig platform than any of the other algorithm-driven ones.