By Chris Maclay

This is the first in a three-part series on global demand. In this article, we explore why employment interventions and jobtech platforms must tap into global demand to create meaningful jobs for Africa’s growing labour force. In Part 2, we’ll examine why the Jobtech Alliance’s systems change approach necessitates intervention to grow global demand for African talent, and in Part 3, we’ll discuss an innovative business model for expanding demand for ICT services in Africa.

In 2007, Marc Andressen wrote a blog called ‘The Only Thing That Matters’. What did he conclude was the only thing that matters to building a successful start-up? Great team? No. Great product? No. Market size? Hell yea. “In a great market,” he explained, “– a market with lots of real potential customers — the market pulls product out of the startup… Conversely, in a terrible market, you can have the best product in the world and an absolutely killer team, and it doesn’t matter — you’re going to fail. You’ll break your pick for years trying to find customers who don’t exist for your marvelous product, and your wonderful team will eventually get demoralized and quit, and your startup will die.”

Demand is everything.

The problem is that demand for labour in Africa is not particularly high.

There are some sectors that will experience significant latent jobs growth in Africa over the next decade; microenterprise, construction, the creative industries, and others. They form the basis of our Investment Thesis for the jobtech sector in Africa. But just adding a tech layer on top of a structural demand deficiency doesn’t miraculously create demand for labour.

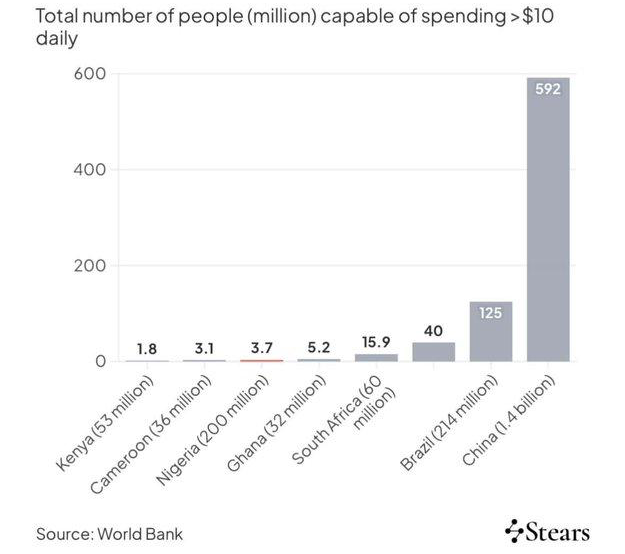

This demand deficiency is driven, more than anything else, by a lack of disposable income of consumers.

These macroeconomic conditions will improve over time, but not quick enough for Africa’s rapidly growing population; 10-12 million young people are entering the labour market each year in Sub-Saharan Africa, and only 3 million formal sector jobs are being created.

So what do we do today? We think it is important to look at the role of global labour markets in the African employment story.

Europe is facing a demographic labour market crisis. And if it’s not facing it, it is ignoring it.

There is not enough talent in Europe and North America to satisfy its ongoing commercial growth. There are currently more than 700,000 unfilled vacancies in Germany alone, including 149,000 in the ICT sector. The stark contrast between labour market surplus in Africa and labour market insufficiency in European markets is only going to increase over the next decade, while Africa will be adding more young people to the labour market than the rest of the world combined.

This creates opportunities for jobtech platforms to mediate between this supply and demand. We will look at two approaches to this: (1) digital, remote, or outsourced work, and (2) well-managed responsible migration. There’s a follow-up blog on international trade somewhere down the line too, but this is quite enough to focus on for the moment.

Digital work

If COVID-19 taught us one thing (other than how to properly wash our hands), it’s that many jobs can be done from anywhere. When Americans moved from their homes in the cities to the mountains of Colorado and were able to keep doing their jobs effectively, it signaled that that same job could be done effectively from the savannah of Kenya.

This applied for high tech ICT jobs, as well as more entry-level customer service roles. With a general move to remote work, even roles like that of the front desk receptionist could now be delivered by someone based anywhere. This global shift coincided with Africa’s rapid growth in the ICT sector and startup ecosystem, where total funding skyrocketed from $1.4bn in 2019 to $5bn in 2022. This gave skilled individuals the opportunity to get experience in fast-paced start-up environments and working on difficult problems.

At the Jobtech Alliance, we observed this shift with great excitement in the belief that, soon, any job could be done from Africa. However, this optimism was short-lived. The launch of ChatGPT in November 2022 demonstrated that many roles previously considered ideal for outsourcing to Africa could now be automated by AI, shifting the landscape significantly again.

AI was not automating (m)any jobs already in Africa; it was just drastically reducing the number of jobs that would ever come to Africa. Western businesses were now optimising for AI rather than optimising for outsourcing.

Enough doom and gloom; we are optimistic that the opportunity is still significant, driven both by the scale of the labour shortfalls elsewhere, as well as the growing capacity of African jobtech platforms to service it. African jobtech platforms are taking a range of business models to respond to this demand:

- Staff augmentation (or ‘bodyshopping’): Tana, for example, trains and places recent ICT grads from Kenya into roles in American and European start-ups, primarily in software QA, tech support, data analysis, and DevOps. Here, the workers are hired by Tana, but placed or seconded to the global companies.

- Traditional ICT outsourcing (or ‘devshops’): This involves outsourcing a project or service, rather than hiring of individual workers. iTalanta in Kenya, for example, builds products and apps for global clients.

- Traditional outsourcing, in new sectors: Cloudfactory, Hugo, and AfricaAI are all leading the wave of AI data annotation for global clients.

- Specialized, knowledge-driven outsourcing in niche sectors: IShango.ai, for example, develops and deploys remote data science teams.

- Freelance and remote work: Platforms in this space tend to be global (Fiverr, Upwork, etc.) as African platforms typically struggle to compete, though some African platforms like Meaningful Gigs have built solid businesses around vetting and quality control within niches like creative services, much like the above managed service companies.

While many of the examples above are in ICT services, they could feasibly exist in any industry from accountancy to animation.

These businesses are not exponential growth scale businesses, but are instrumental in bringing global jobs to the African continent. And we think that these jobs will be quality jobs, providing competitive wages, skill development and pathways to career growth. As our upcoming sector scan on digital work platforms in Africa will explain, we believe that the sector will grow through multiple players building around different niches or specialties.

Above: A Tana team member placed in a European start-up

Migration

Migration is logistically, politically, and even philosophically, a little bit more complicated.

With anti-immigration governments being elected across Europe and North America, you might ask why we’re even bringing up this topic.

But migration continues to be both a critical source of labour across these markets (in 2022/2023, 43% of midwives registered in the UK were trained in low and lower middle income countries) and one of the best – if not the best – tool for economic mobility in the world; workers who find jobs in richer countries can expect to increase their income by 6 to 15 times.

Migration doesn’t quite feel like the slam dunk that digital work feels like though. It feels like we’re turning our back on Africa; taking income outside of the African economy, and accelerating a brain drain of African talent. Commentators would point out, for example, that japa syndrome – mass exodus of Nigerians – is stifling the local ICT sector and the economy at-large, as the best professionals take up the opportunity of tech visas abroad.

The same cannot be said of all sectors, where qualified workers are still failing to find jobs in-country. Germany is apparently hiring bus drivers from Kenya. Kenya could additionally probably export a full year’s worth of accounting graduates and the domestic market would not notice.

The key is intentional and responsible migration. One that facilitates migration in sectors which the exporting country has the capacity to lose, or indeed, where migration will stimulate growth in skills in those domestic markets.

The brain drain hypothesis assumes that there are no market-correcting factors to migration. Evidence from the Philippines shows that for each one nurse who migrates abroad, nine receive domestic qualification; and with the opportunity for quality jobs in international markets, more young people want to get into those trades.

What might this look like in other sectors? The EU, for example, needs 1 million solar installers by 2030. But Africa also needs solar installers. So surely migration of the few solar installers in Africa to Europe would just perpetuate this shortage, right? Possibly, but let’s use a thought experiment.

| A thought experiment: Solar installers to Europe At the Jobtech Alliance, we work with an amazing Nigerian startup called Instollar, which trains solar installers and links them to gigs across Nigeria, including in the most remote regions that need alternative energy the most. The problem that Instollar has, is that it’s pretty difficult to get qualified installers to do installations across the whole country, particularly for the fees that clients are willing to pay. Now imagine a world where migration routes for skilled solar installers to Europe existed; where qualified Nigerian solar installers, who have a track record of delivering quality jobs in Nigeria, could get well paid solar installation jobs in the European Union. More young people would have motivation to be trained in solar installation, and with good market signalling, we’d likely see an uptick in those being trained in the space. Moreover, if Instollar had a migration offering, solar installers would be motivated to complete those jobs across Nigeria that they’re currently unwilling to do, as they seek to reach their, say, 500 jobs with a 5* rating which makes them eligible for the potential global placement. For Instollar, the potential of a sizable placement fee for facilitating international migration (placement fees for international nurses in the UK are roughly £10,000) would also enable them to invest in training themselves, including getting individuals accredited to the necessary EU-level. In this way, migration makes the entire model possible, delivering skilling and strong employment outcomes for users, business model profitability, and a large pool of quality and hard-working solar installers in the Nigerian market. There’s also the fact that Africans are great at sending back remittances (in 2023, Nigeria received approximately $19.5 billion). |

The example above is merely hypothetical. Though Instollar is a real and high potential platform, it does not yet have plans to operate in the migration space. But the thought experiment demonstrates the potential both of jobtech platforms contributing to responsible migration, and responsible migration contributing to the viability, sustainability, and scale of jobtech platforms in Africa.

The labour basket of the world?

Given the demographic shifts taking place, Africa has the potential to become the labour basket of the world. In some ways the destination seems inevitable. The question is just how fast can we get there, and can we do it well.

As these are emerging areas of exploration for Jobtech Alliance, this blog serves as a starting point to provoke thought and encourage deeper engagement. We look forward to collaborating with experts and stakeholders to shape actionable strategies for connecting Africa’s labour force to global demand, including Genesis Analytics in the digital work and outsourcing space, LaMP in the migration space, and the many jobtech platforms in Africa seeking to create quality livelihoods for their users by tapping into this global demand.

The author is the Program Director for Mercy Corps at the Jobtech Alliance

0 Comments