By Chris Maclay

When I joined Lynk in 2017, I was excited about embarking on our mission of connecting millions of informal workers in Kenya to jobs. Millions. I was so excited. This was tech-enabled scale. Or so I thought.

Back then I used to work on the customer service team on the weekends, to learn about the nuts and bolts of how the business operated, and understand the pain points for customers and workers alike. On one of my first weekends I got a very angry call from a customer – let’s call her Barbara. Barbara was unhappy with the quote she had received from a plumber on the platform, Erick. ‘The materials prices are extortionate’, she explained, ‘and I could get someone from the road in Gikomba (a hardware market in central Nairobi) to do the labour for half the price. I called Erick to understand the materials costs. The problem was that the item she needed only came in packs of six, and individual plumbers were unable to negotiate for reduced prices. I called back Barbara to explain, also making reference to the labour cost – the amount she wanted to pay was under minimum wage. Moreover, this was a specialised service, and Erick had been vetted and completed 300 jobs with a 5-star rating. He was not ‘just a plumber on the road in Gikomba’. We reduced our commission to 0% to ‘acquire the customer’, but she still rejected the quote – ‘I don’t want to pay for transport; they can walk’. Erick, a quality plumber coming from the other side of town, needed two separate buses and a motorbike to reach the location. We later managed supply chain, brought on transport partners, standardised prices up front and more, but I learned two things on this day which have followed me in my work with jobtech since: (1) jobtech in Africa will not look like jobtech in North America and (2) scale is going to be much harder to achieve in African jobtech.

Western jobtech ≠ African jobtech

Most gig-matching platforms in Europe and North America were built around one fundamental business model: winner-takes-all. The logic is that one platform can control the whole of (or most of) a sector or industry, with impossibly thin margins enabled by impossibly large scale. With strong technology in place, the logic goes, after a certain point more customers and workers can just be added at near zero marginal cost. Often this has meant that viable unit economics and business viability are not even a consideration for a long period – ‘get to impossibly large scale where you have a functional monopoly, and profitability can be worked out later’. Uber, for example, lost $550 million from operations in Q4 2021, despite reporting 118 million users in the period.

While there may be some doubts about whether Uber’s model will really ever make sense, one thing has become clear over the past few years; the Western tech-enabled winner-takes-all or winner-takes-most model in jobtech is going to be difficult to replicate in emerging markets like Africa. As we saw with Erick’s experience above, the reasons for this exist on both sides of the marketplace:

- Supply-side: As covered in our previous article on operational lessons learned at Lynk, there are such a wealth of supply-side complexities in gig-matching in a place like Kenya. Whereas Taskrabbit in North America primarily solves for information asymmetry and convenience, Lynk was solving many more deep and complex problems on the worker side with Erick: skills capacity, supply chain, communications skills, safety, transport, and more. These issues are not unique to Lynk; as Janet Otieno, founder and CEO at Kisafi (another Kenyan gig-matching marketplace for blue collar workers), explained: “The recruitment process is not easy. There is so much bottleneck in vetting”. Huge investments were required by Kisafi to test technical skills, and work was needed to build capacity of workers to use the platform’s tools: “in the blue collar sector, we had to do a lot of user education. We had an app for gig workers but they didn’t use it.” That was just the start of getting people onto the platform. The real complexity comes from ensuring quality consistent delivery of work. Janet’s experience mirrored that of Lynk; “We saw that electricians and fundis struggled with things like transport of their tools, so we set-up a logistics department.” Logistics departments, design departments, project management departments… Lynk ended up providing all tools and materials, standardising personal protective equipment and work process, building a wood-drying kiln, designing all furniture items (and the list goes on…). All critical elements to deliver on the supply side with quality, but with each extra operational layer, we move further from the ‘nominal marginal costs model’ required for tech-enabled scale.

- Demand-side: Most thriving start-ups in Africa have done so by drastically reducing the cost of something. When the operations outlined above are so significant, most jobtech platforms cannot compete on price of labour, particularly when competing with an illegally underpaying informal sector. While we regularly hear about the growing middle class in Africa, we forget that the ‘fortune at the middle of the pyramid’ lies with those earning $4-8 per day – this does not leave significant spending power to pay for quality and convenience of labour over price. “There’s a challenge when it comes to [the middle class] being willing to pay for premium service,” Janet explained, “people want to pay the same as what they’d pay walking along the road to find a mama nguo” (small laundry service on side of road).

Capturing value in jobtech

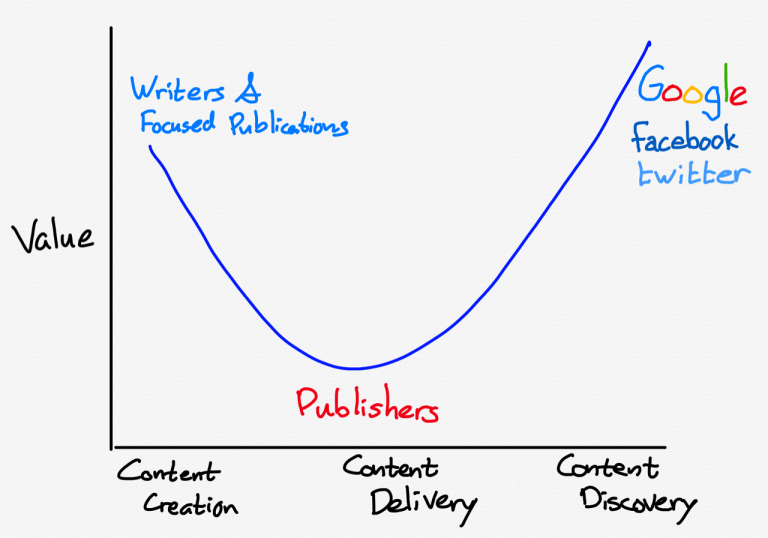

That is not to say there’s no hope in jobtech. Far from it. There’s certainly a wealth of opportunity to achieve scale in the digital work space, but even in these platforms for offline work, there’s multiple avenues for viability. In his article on ‘The Smiling Curve’, Justin Norman from The Flip podcast explains that in many sectors (using the example of media companies), “Aggregators win horizontally, with their massive power over demand. But on the other side of the chart, content creators win vertically, because of differentiation.”

While the graphic above is focused on media and content creation, Norman argues that the model can be used across many different sectors. I certainly think it applies to jobtech; by building really strong niches and going deep in a way that no-one else can, there is great value towards the left-hand side of the above graph. This is what Kisafi has done, reorienting the business around a smaller population of customers willing to pay higher costs: “Why they left is the costs, but why they return is the quality… At the end of the day, our target customers are busy professionals. They don’t have time to go on the road. That means we need to focus on quality. This relies on heavy management of the partners. This means covering things when they go wrong. This is the convenience and the quality.” We may see similar cases of jobtech start-ups going deep around individual verticals from beauty or plumbing, to translation or graphic design.

I would hypothesise that Kisafi’s experience – reorienting the business to smaller niches, where businesses have greater operational backends but greater margins (and viable unit economics from the outset) – is going to be a common model for jobtech in Africa. Not single winner-takes-all or winner-takes-most platforms, but many smaller platforms working on individual niches. And solving deeper worker and customer problems. This provides all the more justification for a forum like the Jobtech Alliance to provide shared learning across hundreds of different platforms.

Charting a route to scale for jobtech in Africa

As Norman summarises the graph, “value accrues to either the differentiated content creators or the aggregators. The middle is the dead zone.” Without effectively orienting to niches, many jobtech platforms in Africa risk falling into the dead zone.

But does this mean that scale won’t exist at all in jobtech in Africa? What does jobtech on the right-hand side of the graph look like? I would argue that it looks a lot like infrastructure: platforms that provide tools for other jobtech platforms or for workers in the future of work. Timothy Asiimwe has written for the Jobtech Alliance about an example of this in portable reputations, as well as pointing to gigworker-oriented financial or insurance products that could operate across platforms. He points out how such models are primed for emerging trends around web3, which seek to offer an antidote to the extractive nature of many of today’s dominant winner-takes-all platforms. Without wanting to sound like a meme, is the future of jobtech in Africa built on blockchain? Who knows. What we’re pretty sure of though, is that more jobtech entrepreneurs in Africa need to start asking where they lie on the smiling curve, and whether they should be focusing more on viable unit economics or scale (or both!). Oh, and more support for those entrepreneurs to avoid falling into the deadzone.

Christopher Maclay is the global Director of Youth Employment at Mercy Corps. He was previously COO at Lynk.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks