By Gituku Ngene

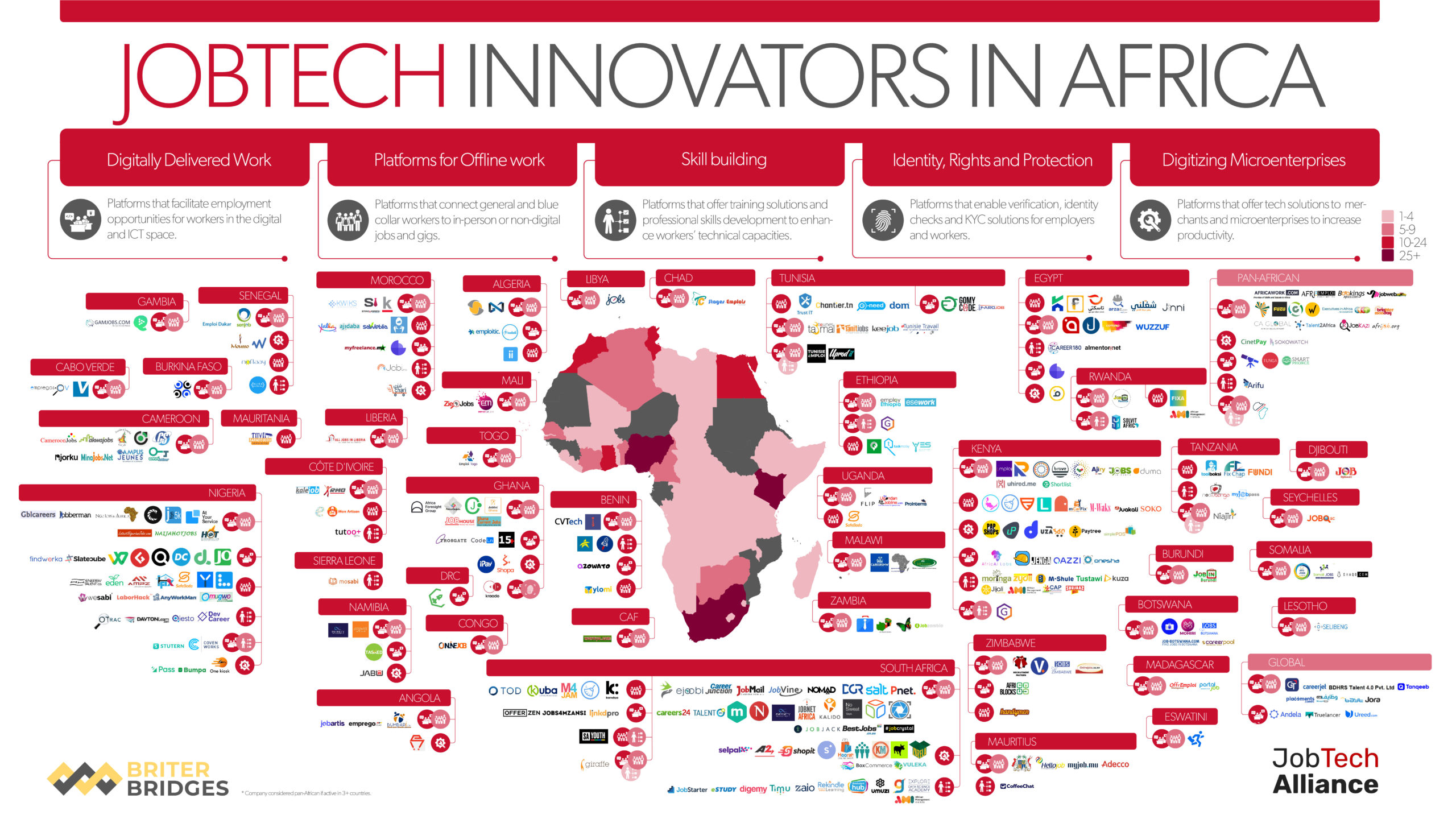

This article summarizes what’s really going on in the jobtech space in Africa: explaining what the key business models are calling out some well-known actors. Remember that you can find a full mapping of jobtech actors in Africa here.

UNCTAD’s 2021 report on the digital economy indicated that mobile broadband penetration in Africa had expanded by twenty times between 2010 and 2020. This expansion has fueled similar growth trends on the continent in sectors such as e-commerce, fintech and EdTech. African markets are experiencing a rapid digitalization across sectors, ranging from education, financial services, tele-medicine, and food production – which all form the pillars of the new digital economy. All these sectors are at varying stages of growth with some like fintech approaching maturity. In this context, the digital transformation of labour markets in the region is a more recent phenomenon, but one that has seen attention-worthy activity over the past 5 years. With huge un- and under-employment on the continent and a bulging youthful, tech savvy and well-connected population, it is inevitable that the internet and work platforms will play a much more central role in the labour market in the future.

The rise of digital work in Africa has some parallels with shifts in Western markets, characterised by emerging platforms like ride hailing solutions, delivery services, and freelancing. But there are also significant differences. Differences in the types of matching solutions, differences in users, operational challenges, business models and more.

There are also differences in narratives. While the growth of digital platforms and the gig-ification of the economy in many Western markets has raised a lot of concerns about security and quality of work, the rise of comparable platforms in many African markets has been met with more positive interpretations; about opening new opportunities for informal workers or micro-entrepreneurs, creating access new markets, formalisation of informal trades, and the generation of greater incomes and revenue. The likely main reason for the difference in narrative is that the formal jobs with benefits which were ripped apart in Western markets never existed (at scale) in most of Africa, which is predominantly anchored in the informal market. In Kenya, the informal sector employs as much as 83.6% of the workforce, for example. Therefore, Africa’s unemployment challenge has built a strong case for the rise of work platforms as a driver for job opportunity.

This article doesn’t seek to argue either side of this debate, but to present the divergence in context and narrative, and to present the question: what really is jobtech in Africa?

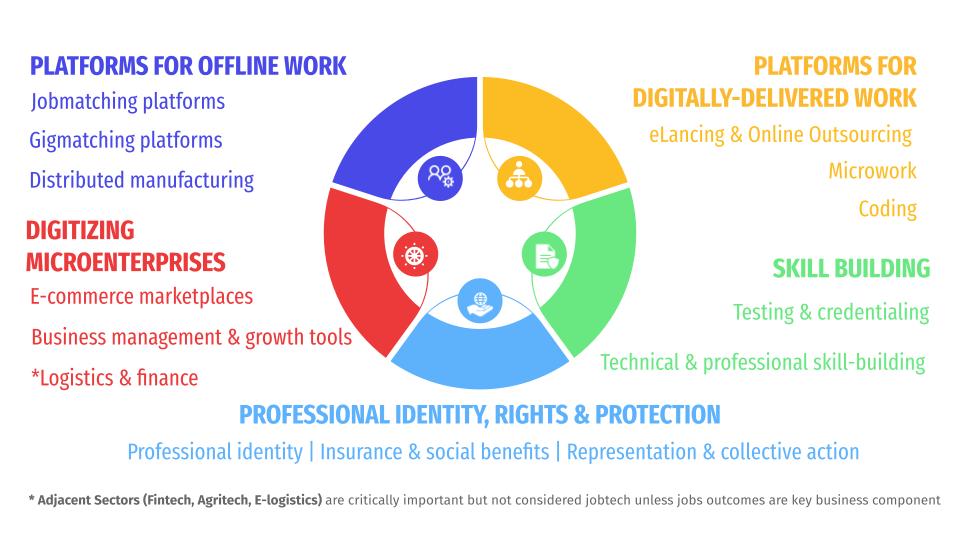

Let us begin by demystifying the term Jobtech. Jobtech involves the use of technology to enable, facilitate, or improve the productivity of people to access and deliver quality work. A recent mapping by Mercy Corps and Briter Bridges indicated that there are over 300 Jobtech platforms in Africa by July 2021. What’s interesting is the diversity of these platforms. Jobtech covers a broad spectrum and can be divided into five major buckets as outlined in the diagram above. The evolution of the Jobtech ecosystem in Africa can be mapped along these broad categories as we shall discuss in subsequent sections.

Platforms for offline work – digitizing an offline market

According to a Mercy Corps report on the gig economy, the concept of offline gig work is not at all new to African markets. Workers in the informal sector have for decades engaged in work only for specific periods of the year or worked on a casual labour basis where they are paid per task or per day. However, digital platforms (also referred to as ‘location-based platforms’ by the World Bank, ILO and others) have transformed these interactions between employers and workers by digitising the matching process, expanding opportunities e.g. connecting workers with work outside their small communities or/ and across socioeconomic classes, and opening up new markets. One such platform in South Africa is SweepSouth, an online platform that simplifies the process of accessing reliable and trusted domestic cleaners. Founded in South Africa and with a workforce of 1.2 million registered cleaners, the platform raised US$ 3.9 Million in 2019 and has recently expanded into Kenya. Platforms like SweepSouth are leveraging the domestic cleaning market – analysts have indicated that this market could be as large as USD 4 Billion in South Africa alone. Kandua, a peer platform, has a wider remit around home service providers in over 100 categories. These businesses either operate as ‘lead generation’ businesses, earning revenue by helping to shortlist or facilitating a match, or as ‘full service’ models, managing the full service delivery and earning commission.

Beyond the blue-collar gig matching platforms are job matching platforms, which target a slightly different market segment. Most job matching platforms like Shortlist aim to connect employers to potential workers by addressing search frictions, skill mismatches and hiring complexities characterised by traditional hiring approaches where past experience and education levels are viewed as indicators of competency. Instead, these platforms are looking to use non-traditional learning experiences, which are particularly relevant for most emerging markets where formal tertiary education is very limited. At a global level, platforms like LinkedIn, Workday and Recruit (Glassdoor and Indeed) have dominated the global job matching market. In Africa however, we are witnessing the rise of locally led and focused job solutions. Job boards like Brightermonday and Jobberman among others have gained significant traction in key African markets like Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, and South Africa, and our mapping with Briter showed that there are jobs boards in every market in Africa.

But these only solve one part of the matching platform, which only counts for so much when there are deeper challenges in the recruitment value chain. There has been an increasing emergence of solutions which seek to offer further services beyond matching. Fuzu in Kenya, for instance, has embedded a learning solution, Fuzu Learn on their platform that allows job seekers to enlist for courses and enhance their skills in various areas. Shortlist has experimented with career coaching for young jobseekers. Giraffe in South Africa (now SA Youth), also now allows job applicants to develop their CVs and take upskilling courses through a mobile application.

Distributed manufacturing has experienced the slowest traction amongst the offline work categories. Shop Soko is one such solution that enables a distributed network of jewellery makers in Kenya to get access to orders of standard products. The rise of technologies such as 3D printing promises to transform the concept of manufacturing and bring sophisticated manufacturing solutions closer to African markets. Experts point out that manufacturing holds potential to pull Africa through the post-pandemic recovery and is projected to hit USD 666.4 billion dollars by 2030. Having even a fraction of this go into distributed manufacturing could transform the livelihoods of thousands of workers across the region. However, the sector continues to face challenges in quality control, consistency in outputs and addressing worker safety – critical issues that will need to be addressed as the sector grows.

Platforms for digitally delivered work

Traditional freelancing was the genesis of online work, with global platforms like Upwork, Guru, Fiverr among others, mainstreaming the outsourcing and redistribution of work into tasks that are commissioned and mostly carried out virtually. These platforms advertise specific tasks on platforms, which can then be matched to suitably skilled crowd workers. According to a 2020 report by Grand View Research, the global digital workplace market size is expected to reach USD 54.2 billion by 2027, with an annual growth of 11.3% (The Online Labour Index provides a slightly damper outlook of 4.5%). Covid-19 has only accelerated this process, with increasing remote work and distributed teams. This is especially important for Africa where the unemployment crisis is really a question of missing jobs. While these types of platforms are originally geared on creating efficiencies and lowering costs in other markets, they are unquestionably distributing work to emerging markets and in the process creating a new category of imported jobs on the continent. Studies estimate that Africa holds between 4.5% (Online Labour Observatory) and 10.1% (Payoneer) of the world’s freelancers – a number that is expected to grow in the coming years.

However, Freelancers in Africa have protested at being blacklisted and systematically left out of opportunities by international platforms. In fact, workers have figured out work-arounds to address this. From a past Mercy Corps study, workers highlighted that they have resorted to using VPNs to change their internet locations to markets like Australia or Canada, which unlocks larger quantities of quality work opportunities for them. As a counter to these trends, a rise in African-based and African-foused platforms like Tunga, Hugotech and Meaningfulgigs is bringing the opportunity closer to young Africans on the continent.

Even as the freelancing ecosystem faces such challenges, workers are turning to other models of distributed online work. The rise of businesses that deploy distributed workforce solutions for machine learning and business process optimization is one such area. The micro-distribution model, which is primarily a crowdsourcing model, distributes microtasks through platforms that allow workers with minimum qualifications to deliver on complex tasks which are broken down to small, individualised tasks. This allows workers to secure work with limited or no training, choose the type and amount of work to engage in at any given time, and work from anywhere – including using their smartphones through platforms like Appen, Scale AI and Corsali. According to Allied Market Research, the global data annotation industry is set to grow from $1.4 bn in 2020 to $30.7bn in 2030 due to the rise of big data and artificial intelligence technologies. In East Africa, local companies such as Africa AI Labs, Kaziremote, Sama, and CloudFactory are building a managed workforce of young workers to undertake tasks such as data labelling, annotation, transcription, translation among others. In such cases, some companies have mobilised workers to work within a defined physical or virtual spaces and prescribed working hours. This often allows them to have better quality control, guaranteeing timely and high-quality execution of labour.

Finally, emerging solutions built on the blockchain offer a range of future earning possibilities such as play-to-earn, as has been highlighted in one of our previous articles. This article explores the opportunities in this space in more detail.

Digitising micro-enterprises

Probably the most vibrant bucket within jobtech, certainly from a venture capital perspective (in August 2021, Techcrunch called it ‘the second-best thing after fintech at the moment’), are platforms that provide avenues for small and micro-enterprise vendors to enhance their sales, inputs, logistics and fulfilment and payments. These enable retailers to sell their products online by providing marketing solutions and delivery infrastructure that they often would not be able to invest in on their own.

E-commerce in Africa has steadily grown with the number of online shoppers growing annually by an average of 18 percent, compared to the global average of 12 percent. According to a recent report by the IFC, the sector has a potential to reach US$ 84 Billion dollars by 2030. However, majority of this market is still controlled by large e-commerce giants like Jumia, Kilimall, Konga and BidorBuy among others. On the flipside, a large fraction of the region’s retail market is still informal – characterised by millions of micro-traders who depend on traditional sales and marketing models to grow their customer base. The rise of digitization solutions is an opportunity to transform the sector by formalising retail trade and unlocking opportunities. Sky Garden in Kenya anchors its models on creating a virtual shopping mall, allowing small and micro traders to create their e-commerce stores. This allows these traders to leverage the platform’s marketing, fulfilment, and payment mechanisms to establish an online presence.

Alerzo, a rising B2B e-commerce retail startup based in Ibadan, Nigeria, focusing on digitising the operations of mom-and-pop stores recently raised a $10.5 million Series A round. In Kenya, Sokowatch has grown significantly expanding into neighbouring markets in Uganda and Rwanda, while Twiga Foods is set to scale its supply chain solution that connects farmers to vendors and informal outlets to East and West African countries.

Skill building platforms

Given the poor education infrastructure available for young Africans, access to quality skill-building opportunities are still a major challenge for those aiming to enter the workforce. Even where such opportunities exist, they are often ill-equipped, have archaic, unapdated pedagogies and often do not match the evolving demands of the current and future workplace. E-learning platforms have come as a great solution offering various online courses for skilling and training in new-age technologies allowing existing and new workers to learn through mobile phones, tablets, USSD and SMS, and apps with digital content, gamified learning, and even personalised learning. Yet the vast majority of edtech has focused on primary and school-based education, with few solutions that have truly taken off focused on the world of work.

Further, the Covid pandemic has rapidly accelerated the uptake of online education, with more learners and workers, especially young ones, turning to e-learning platforms to skill and upskill themselves. According to Linkedin Learning, 67% of Gen Z learners said that they spent more time learning in 2020 than they did the previous year. This demand for short-term digital upskilling surged from mid-2020 and has continued to peak. However, Africa continues to lag behind in terms of innovation, uptake and investments in the e-learning space. According to HolonIQ, Latin America, the Middle East and Africa represent just under $1B of the USD 30 Billion investments globally in post-secondary learning and earning over the last five years.

Chalkboard, a Ghanian e-learning platform has provided learning support to over 12,000 users across multiple African countries seeks to provide an off-the-shelf solution that can deliver training affordably through customised digital training. Africa Management Institute has a blended learning model to build management and entrepreneurial skills. Other examples are Zydii, an end to end digital training platform enabling businesses to offer digital training through localised digital courses and Slatecube which has focused on building intelligent SaaS platforms for learning and workforce development.

There is still a major gap in Jobtech solutions focused on skilling the informal market. This section of the market has been overlooked, despite employing up to 80% of workers in markets like Kenya, Uganda and the majority of the other African countries. Mosabi is an African company trying to solve this challenge by not only focusing on skilling informal sector workers, but also providing them with access to finance so that learners can start their own micro-enterprises once they are equipped with the skills.

Professional identity, rights, and protection platforms

As the Jobtech ecosystem grows, interventions around worker identification and protection will emerge to strengthen the sector. Though we see little currently in this space in Africa, if we look towards more developed jobtech ecosystems – in Europe, Latin America, and North America – we see more solutions being built as the ecosystem matures. This is largely because these tend to be built on top of job matching and gig platforms.

On identity, global examples have shown the potential for platforms are that can address worker vetting challenges, which allows platforms to establish the authenticity of workers on their platforms. Solutions are also stemming up to address the issue of worker protection and financial security. In certain instances, work platforms have set up in-house solutions, while in others they have preferred to collaborate with independent financial platforms to model such solutions. In the case of Sendy, the platform partnered with an insurtech, Lami Technologies, to develop an in-transit insurance solution for its riders and drivers. SafeBoda has a broader spectrum of solutions developed in collaboration with partners such as Watu Credit, Turaco, Allianz, and D.Light to offer welfare-enhancement products ranging from health insurance benefits to home lighting solutions. While these are not Jobtech solutions, they offer a reference point to the potential solutions that could emerge out of this space. Increasingly fintech partners are modelling their services to target digital workers and provide bespoke financial and welfare products. ImaliPay, a Nigerian-based fintech, is leveraging artificial intelligence and big data generated on digital platforms to offer tailored financial products for workers. Pezesha, a Kenyan-based start-up is also focusing on the gig economy and e-commerce spaces (and MSMEs more broadly) by building worker profiles, educating borrowers and unlocking financial products for gig workers and other MSMEs.

Overall, this descriptive account outlines our current characterization of the Jobtech landscape in Africa, which comes across as rich and diverse, despite being in its early days. However, we are yet to see a full scale of solutions – which is partly attributable to the nascent nature of the sector and the absence of a strong ecosystem to nurture these platforms. We expect it to evolve with time as the sector continues to mature and anticipate more players (especially innovators) crowding in over the next few years. The Jobtech Alliance has been established to address this gap, and is poised to bring together entrepreneurs, funders, policy makers and other support organisations to drive collaborative action towards building the Jobtech ecosystem.

The author is the Senior Advisor for Youth Employment and Innovation at Mercy Corps

0 Comments